Recently I was asked to present and lead a discussion of the first film in a new series* at the Busch Annapolis Library. The event is called Immigration Stories, a four-film series exploring the plight of immigrants in America in various places and eras. My good friend Ann Glenn, who put the series together (and will present the next three films), contacted me a couple of weeks before the first event, telling me that she was going to be unable to kick off the series and asking if I would be available. I was glad to accept.

The first film for the series would be Gran Torino (2008), directed by and starring Clint Eastwood.

Ann and I met to discuss the film and how I might prepare not only for it, but also for introducing the series to the audience. Ann is a knowledgable and enthusiastic cinephile who has presented films in the Annapolis area and beyond for many years. She also has quite a following, bringing in some serious moviegoers to her programs.

It can be a bit unnerving speaking to someone else’s regular audience (somewhat like being a substitute teacher), but I knew from attending several of Ann’s previous presentations that her group shared at least a few people from my Severna Park Library audiences. I know my local people, and Ann knows hers, but when you’re a guest presenter you’re never really sure what to expect, especially with a potentially off-putting film like Gran Torino.

If you haven’t seen it, Gran Torino is the story of Walt Kowalski (Clint Eastwood), a recently widowed Korean War veteran who finds himself in an aging, decaying Detroit neighborhood filled with Southeast Asian immigrants and gang violence, a neighborhood that was once filled with working class white families. Walt is mad at the world, mad at God, and mad at his next-door neighbors, spouting all kinds of racial degradations at them. We sense there’s going to be more conflict.

Not knowing how many people would be offended by the film’s use of racial and ethnic slurs, as well as hostility to immigrants in general, I felt I had to give this audience a caveat. With every film you watch, I told them, someone (the writer, director, producer, etc.) is making a decision about what you see and how you see it. All such decisions are manipulative in some manner because choices must be made in every scene in every film: setting, background, camera angle, music or no music… The choices are legion. Often those decisions are designed to make the audience feel a certain way.

I warned my audience (primarily senior adults) that they may be uncomfortable, maybe offended. But I encouraged them to push through to the end. Everything in a film happens for a reason.

As we watch, we’re also learning something about the film’s characters. Why do they behave this way? Is their behavior justified? Is it reactionary? Of course you can analyze these things to death, but upon a first viewing (which it was for the majority of my audience), you try to consider those questions.

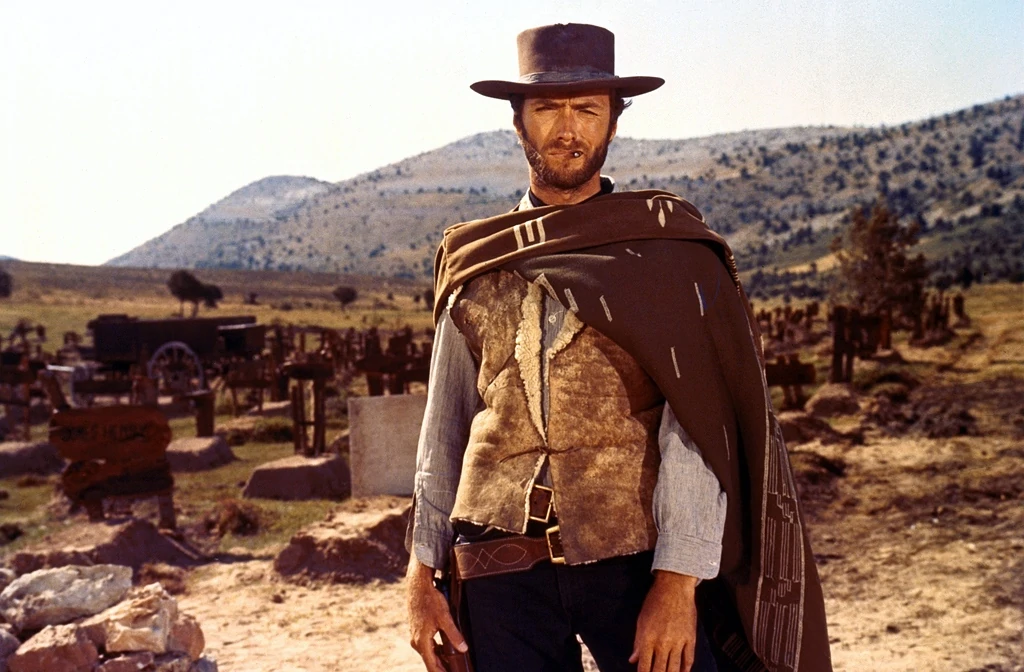

I also wanted to let my audience understand that Eastwood made many memorable Westerns and crime pictures in his 65-year (and counting) career. Most people of my age remember Eastwood’s personas of The Man With No Name and Dirty Harry Callahan. Those characters are familiar and carry a certain expectation.

But something happened in 1992 that changed Eastwood’s persona. What happened was the film Unforgiven, which Eastwood starred in and directed. Even casual Eastwood fans knew there was something about that picture that was different. Most of Eastwood’s Westerns were not typical action pictures set in the West, but this one had something important to say (not that the previous ones didn’t). It felt personal, especially the first time we hear Eastwood’s character Will Munny say “It’s a hell of a thing, killing a man. Take away all he’s got and all he’s ever gonna have.”

We’d never heard anything like that from an Eastwood character before. It’s a far cry from, “Go ahead, make my day” or “You’ve gotta ask yourself one question: ‘Do I feel lucky?’ Well, do ya, punk?”

If Unforgiven overturns Eastwood’s Western image, Gran Torino at least challenges his law-and-order-by-any-means-necessary cop image. If you grew up with those early films, like I did, you know - or think you know - where Eastwood is going, what he has up his sleeve. But, as I told my audience, if you haven’t seen a Clint Eastwood film in a while, you may be in for a few surprises.

I encouraged my audience to look for a few things while watching the movie:

Watch how people greet each other, what they say and their body language. Look at who they are and where they are, not only with respect to the film’s staging, but also in their lives.

Think about what the cars in the film say about the characters who own/drive them.

Pay attention to the camerawork and music, how they help convey character.

Post-Movie Discussion (SPOILERS)

Because I was presenting in a new location, didn’t completely know my audience, and wasn’t sure how much time we would have for discussion, I pointed out a few things that they may have picked up on:

We often see characters placed or framed in positions of power or vulnerability. Walt appears in both: He’s a rugged, proud individual who frequently stands (with or without a firearm) like a sentinel, sometimes shot slightly from below to give him more gravitas. Yet at other times he’s shown as small and vulnerable due to his age and health.

Walt’s Hmong neighbors are generally shown as vulnerable and helpless, like children who can’t take care of themselves in this environment. This idea is most developed with the character of Thao (Bee Vang)+. This situation, of course, prepares us to accept Walt as the white savior (and many audience members commented on Walt’s Christlike death at the film’s end).

These are not-so-subtle aspects of the film that I wanted to get out of the way in order to focus on some other elements that may not be so obvious, such as a decision Eastwood makes as far as staging:

Eastwood creates a handful of shots in which Walt is placed on one side of the screen, usually berating his neighbors. On the other side of the frame, we see the American flag hanging from his house, which carries the idea that Walt’s racial slurs and attitudes are a part of who America is. Yet when Walt decides that Thao can borrow his beloved Gran Torino for his first date with Youa (Choua Kue), Walt is placed on one side of the screen as before, yet the American flag is absent. Walt has broken away from his former manner of looking at his Hmong neighbors. (Interestingly, we also see the flag when Father Janovich [Christopher Carley] challenges Walt.)

When I prepare for these presentations, I normally have far more material than I’ll have time to use. In the past I’ve had both very chatty audiences and groups who wouldn’t utter a sound if you lit a fire under their chairs.

This group had some excellent thoughts on the use of music, comic relief, setting, and more. Some shared their own experiences of changing neighborhoods and what it was like not only for them, but imagining what the immigrants themselves were feeling. We had many comments on how Walt’s war experience led him to become the man we see at the beginning of the film and how he uses that experience to rethink a few things. White savior elements aside, Walt does sacrifice his life for the betterment of a neighborhood where he’s the minority, but he’s also saving Thao’s life.

I was fortunate to have a great audience for this film. It’s not always this way. Perhaps in a future post I can discuss how to handle audiences that are indifferent or even hostile toward certain films. If you’d like to read about that, let me know. Thanks for reading.

*Other films include Goodbye Solo (2008), Entre Nos (2009), and Minari (2020).

+ Vang, who initially praised the film and its treatment of Hmong characters, has since spoken out against the film.